I felt great as the race started. It was as if my mind took the beginning of the race as the culmination of the training and wanted me to celebrate this occasion. I think that part of my mind was a bit premature in celebrating. Having said that, the start was pleasant. The pace was reasonable until the neutral start vehicle pulled away at the start of the gravel just outside of Emporia. At that time, the pace picked up noticeably. I felt comfortable pushing the pace a bit, wanting to stay in the main group as long as I could. As we approached the 20-mile mark, the leaders started pulling away from the main pack, but the pace remained high in the main group. The Slate was working flawlessly, the weather was fantastic. I’m sure birds were even singing. Then, pfft-pfft-pfft-pfft-pfft…I look around wondering whose tire that might be, and my 180-degree glance is no more than half done when I feel the back tire getting squishy.

So much for the singing birds. I wave a quick goodbye to my teammate Ian, and pull off to have a look. The rest of the main group steams by at 20 mph, like a herd of bison on the grassland prairie. I see the 3-5mm cut in the sidewall of my Schwalbe G-One tire, sealant oozing out and do my best to see if the sealant will do its magic. Shake wheel, pump in some air, shake again, pump again, put the bike down and test. Or some other sequence of these actions – it’s all a bit hazy as some of these actions in hopes of sealing the cut may have been done during a short temper tantrum. No such luck, as soon as I try to increase the pressure, the air starts escaping again. Off comes the wheel, in goes a tube. Remain calm. Quick fill from CO2, wheel back on and get back on the bike. Nine minutes. Nine minutes is an eternity in the early part of the race when the large groups are still together. As I pedal away, I manage to find a positive state of mind, telling myself that there are almost 190 miles left to make up time. I get in the drops of my Easton AC70 AX bars, put my head down and start working. I bridge gaps between riders and small groups, taking small breaks every now and then before going for the next gap. This clawing back continued for the next 90 minutes/45km as I try to make the most of leg 1 before pulling into Madison for the first aid station. Sadly, I had made up positions, but my pace had not been any faster than that of those that I had originally been racing with. I arrived In Madison to be greeted by Robin and Joanne, with my team-mate Ian already long gone to leg 2.

If one were to spend hours analyzing the data on the Strava Fly-by Analysis page, one could conclude that recovering from being nine minutes behind was tricky at best once working mostly alone. In fact, all I had managed to do was keep pace with the group that I had been riding with, arriving in Madison close to 10 minutes behind. Once in Madison, I received two full bottles and a full Camelbak, all filled with GU Roctane. These replaced the three bottles I had started with, now approximately half empty. The leg had been cool and relatively fast, nor had I felt hungry as I had not touched any of my GU gels or chews. Robin helped me change the rear wheel to a spare (actually off of Robin’s Slate) so I could resume the journey with two tubeless tires and full of hope. With the extra fussing involving the wheels swap, the stop took nearly 10 minutes. Yeah, we aren’t at F1 levels of efficiency yet.

I pedalled off to leg two, knowing that I could really use a few other riders who were looking to make up a bit of time. Nada. Nothing. That’s what I found for the first half of this leg. This was continued payback for failing to remain in the faster groups at mile 20. At least my mental game was improved. I had made it to aid 1 with my tubed rear tire and now rolling tuneless was full of confidence and was determined to just keep on pedalling at a pace I felt I could sustain for the next ummm….ten hours or so.

In 2015, on our first trip to Emporia, I had an objective of finishing before sunset. This just seemed like an appropriate objective for one’s first DK200. The conditions caused me to miss that objective, finishing in 15:10:45, good for 63rd overall and 10th in my age category. Naturally, for our return, I had trained smarter and harder, I knew what to expect (I really thought I did) and I had retired the beloved Ridley X-Fire in favour of a Cannondale Slate CX1. It had worked for Ted King, so it must work for me (it did, and my body thanked me for it).

After the flat at mile 20, it had taken me the rest of leg one to really calm down. I hadn’t suffered a single flat in 2015, it seemed cruel and unusual punishment to have suffered on so early. But I now on leg 2, I was content to keep working away at gaps and by the second half of leg 2, I seemed to have found some pace again. I had reached the first checkpoint in Madison 15 minutes behind the leader 20th in my category. By the end of leg 2, as arrived in Eureka, the gap was 25 minutes and I was 11th in my category. And, I was starting to feel good. It was also my first sighting of Ian since that sidewall puncture at mile 20, as was rolling out of our aid station about the same time as I arrived.

The stop at aid 2 was relatively quick. Replace Camelbak and two bottles with fees Roctane, and replenish my first food I’d eaten – one package of GU chews, and one GU gel. Not a big eater. Back out and feeling I can make some hay. As leg 3 got under way, the day was getting noticeably warmer. Now worries, I can deal with heat. I remember heat from the summer of 2016. I think.

Spring of 2017 was a cold one in Ontario. Back in 2015, I recall doing much of my later DK training, in May, in hot weather, easily around 30C. This year, I hadn’t done an outdoor training ride without a vest, cold hands and toes, and the odd unscheduled stop at a coffee shop or gas station to warm up my hands in the bathroom hand dryer. But heat is heat – if you’ve dealt with it once, you’ve experienced it and know how to deal with it. Or not.

I pushed on thorough the leg, hoping to make up some more ground by the time I would get to Madison. I was enjoying the roads and the terrain, my speed was good, but I was hot. Hot, but managing the heat and watching my hydration both for sufficient drinking and for managing the reserves. Then, around mile 125….pffft-pffft-pffft.

How is possible? Again? I stopped in the bottom of a set of fast rollers, looked at the sealant oozing out of the sidewall and once again, attempted to shake and wiggle the wheel (still attached to the bike) to see if it would seal. It would seal momentarily, but as soon as I put the bike on the ground and applied either pressure with the pump or my weight on the bike, the leak would open up. Time for a tube. As I fussed with the tire, stationary, the ambient heat became much more noticeable, and I had to keep hydrating as I fixed the tire. Suddenly I was feeling a bit off, body was full of chills, and I sat down to work the tire repair. Tire on, filled with (my last) CO2, and roll away. Not feeling great. I’m sure I’ll feel better soon. Wait, what’s that sound?

I don’t quit races. I don’t even think about quitting races. I don’t necessarily place well, but if I’ve started something, I’ll finish it. But suddenly, I found myself only a few scant metres from where I had just fixed a flat, with another flat. Demoralized, I watched riders go by at high speed as they descended one roller to carry speed to the next climb. I decided I would never race my bicycle after this day. In fact, I may just not ride a bicycle again. I had reached that point.

I had one more tube left. What if that tube blows? Why had this tube failed? Had I missed something embedded in the tire? Back to sitting in the sun, working on a tire, getting hot, and drinking away at my Roctane. For the first time, I found myself thinking about quitting. Whatever time I may had clawed back since the flat on leg 1, was once again gone. And more. I spent nearly 20 minutes with this double tire debacle, in my heat fatigued state, not working smart or efficient, before I was rolling again. The body was shivering with chills, and only the remoteness of that part of the race course and the distance remaining to aid 3 kept me from quitting. I rode gingerly towards aid 3. How does one ride “gingerly” in the Flint Hills? I don’t know, but I could not suffer any more tire troubles before Madison, for I had no more tubes.

After a few minutes had passed and I was again more focused on my race than the drama of tires and goosebumps, I started doing the math on the distance and time remaining before aid 3 in Madison. Suddenly, I was concerned about my Roctane reserves. I had consumed much more than expected, and keeping the Camelbak hose in my mouth as I worked on those tires had clearly been a bad idea. From the tire debacle around mile 125 to around mile 145, I was feeling somewhat confident of my supply situation. I even ate a package of GU chews as I pedalled in the afternoon heat, continuously doing mental arithmetic.

Although I was (by some strange miracle) accepted into, and even graduated from an engineering program, math was never my strong suit. I probably should have started endurance racing at a much earlier age, for all those hours on the bike seem to get eaten up by doing mental arithmetic. There are many variables at play; elapsed time, time of day, current speed, average speed, total distance, distance from last aid, distance to next aid, volume of fluid reservoirs, volume consumed, volume left until next aid, and so on. Add to that the excitement of unit conversions – how many mL are in fluid ounce, what exactly is 42 miles * 1.6309 miles/km? Is that a lot or a little? Did I carry the three? Repeat the calculation to confirm.

With about 20 miles left in leg three, the longest by distance and by time, I had confirmed through multiple equations, that my fluid supply was running really low. In fact, I know my 1.5L Camelbak was as dry as the desert where Camels come from, one of my bottles was completely empty, and the second bottle may have had about 20% of its 26 fluid ounces (or is it 750mL, which isn’t actually the same at all!) left. The remaining Roctane, aptly of the Tropical Punch kind, sloshed around the bottom, as if it was teasing me to just gulp it down. At this time, I had caught up to Garth Prosser, who was not having a great day either. We commiserated about our depleting fluid reserves, and by the time there were ten miles left in leg 3, we were both running alarmingly low.

Ten miles seems like such a short distance. Seriously, 16.309km is just a hop away, who needs to drink? We did. After nearly eleven hours of racing at a good clip, some of it at what my Finnish-Canadian body would refer to as high heat, constant topping up of the system required. I started thinking about asking other racers for fluid assistance, but alas, there weren’t a whole lot of others around us. We kept pedaling, taking turns pulling at what had suddenly become a diminishing pace, barely averaging over 20km/h in these miles of thirst.

Suddenly, as we descended a hill on Township Road 232 towards a t-intersection with Township Road 213 (I had no idea of the names, had to look up on Strava), we saw a rancher and his family, camped out at the intersection with a cooler of water. It was the closest thing to Christmas I had seen since Christmas. We stopped, happy, relieved and thankful, had a quick drink and refilled one bottle for the remaining six miles to aid 3. Our spirits were lifted and we pressed on.

Arriving at aid 3, I beelined for the chair, for the first time. I was no longer concerned about my time, or my placing, I needed to cool down and re-hydrate for the last leg. I was now just over an hour behind the leader in my category, and dropped down to 17th position. My team-mate Ian was still at the aid station, it was clear he was feeling the effects of the heat as well, but he rolled on as I sat down for my well-deserved rest. I wanted to go into those last 50 miles feeling good (relatively speaking) and enjoy the feeling of nearing the end of a long, memorable day on the bike. Robin stuffed the back of my jersey with a pantyhose full of ice, and covered my now un-helmeted head with ice-cold towels. I drank some water, ate some watermelon, and collected my psyche in preparation of getting on the bike. Robin offered to replace my rear wheel with my now newly-tubeless-tire-equipped wheel that had been pulled at aid one. I declined, after taking a little while processing the decision in my head. With only 50 miles to go, I no longer wanted to fuss with the bike, I just wanted to pedal to Emporia.

I had spent ten minutes at aid 3 cooling down, and although it was much longer a stop than I had hoped to stop for, but I had needed some cooling assistance. It was now past 5pm, and the radiant heat from the big ball of fire in the sky was diminishing. The temperature remained high, but I no longer felt like I was stuck in an oven under the broiler. I rolled out, feeling like a new man. It is hard to explain how much better I felt after hydrating, ice packs, cold towels and now, a full Camelbak and two bottles full of Roctane on board. I did much math and confirmed that I should be able to finish somewhere around 13.5 hours or less, assuming no more troubles with tires or other hiccups. I worked mostly alone for the first 20 miles of this last leg, making up some ground in my refreshed state. I hoped to be caught by a faster group to work with, but I couldn’t wait to see if it was going to materialize. Around the half-way point of the leg, a group caught up to me, and I latched on. My speed picked up a bit now that I was working in a group, and I managed to get a little rest. With only about 25 miles to go, my mood was positive and I no longer worried about my bad luck with tires throughout the day, nor was the heat of just a few hours ago much more than just a fading memory. The mind had flipped over to victory mode.

Everyone who toes the start line at the Dirty Kanza is a winner in my book. Just to commit to the effort and roll out of Emporia at 6am makes you a winner. Beyond that, the day is full of little victories of minor battles (and sometimes, little defeats), but once the end is near enough that one can sense it, the impending sense of victory in the war is palpable. For most of the racers out there, it isn’t about podiums and hardware, but it is about testing your body and your mind to its limits, about chasing those demons off your shoulder when they are egging you to quit. Dirty Kanza racers don’t come to Emporia to quit. Sometimes, stuff happens and one is left with a DNF, but no one starts the day with the thought of quitting, if the going gets tough.

As we approached Emporia, the course took some turns away from the city, but knowing the course length of 206 miles, I kept focused on that. I counted down the miles, converted them to kilometres, though about how far that would be at home “hey, that’s just like riding from home to work – just a commute left!”. This from the guy who has commuted to work on his bike maybe five times in the last five years. As we entered the last three or four miles and the road became permanently paved, I quietly started to believe that I would have no more tire trouble on that day.

Thirteen hours, fifteen minutes after rolling across the start line, I was back on Commercial Street, now eyeing the course lined by cones and spectators. I put in my best effort of a sprint finish and crossed the line, to be greeted by Lelan Dains and Jim Cummins. This the Dirty Kanza – the race directors congratulate all finishers at the line, whether your personal victory happens 11 hours or 21 hours (there has to be some cut-off!) into the race. It really is a special event.

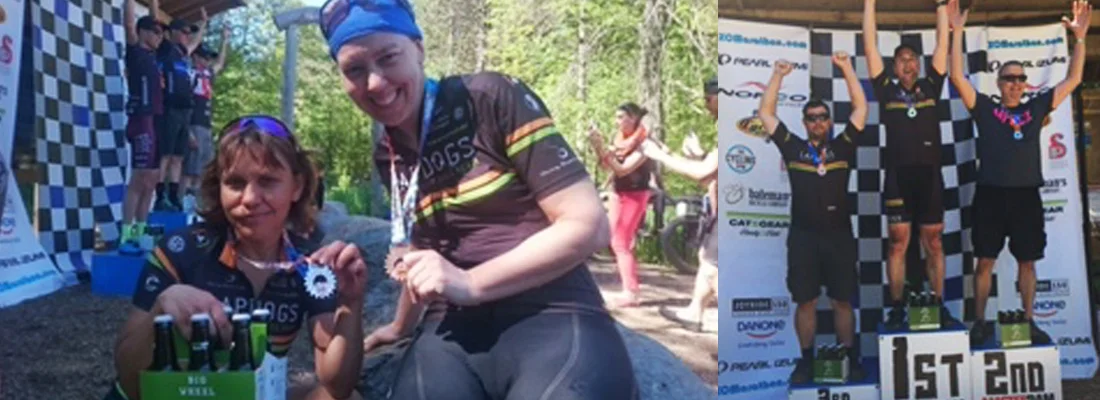

Once I had my finishers pint glass, 200 mile sticker, and race the sun badge in hand, I hobbled out of the finish corral to find Robin for some special hugs and kisses. She was the woman behind the man. She had committed to my training over the winter and spring as much as I had. She had engaged our coach, Peter Glassford, to formulate a training plan for me as a birthday present back in November and she had taken care of the household chores and hiked with Bruno, when I was in the basement on the stationary trainer, or outdoors putting in spring miles. Even our winter/spring bike traveling vacations became all about my training plans. Robin really deserved the finishers swag as much as I did.

My finish time was almost two hours faster than my 2015 effort in the mud. This time, the challenges had been different. I was very happy with my effort, I had left everything out there, gone to my dark cave on leg 3 and climbed out of it for the last leg. That is how it should be. My placing wasn’t what I had hoped it might be, but the DK200 isn’t really about placings for 90%+ of the people. It’s about going out there, leaving it all out there and, hopefully, coming out of there to cross the finish line in Emporia 200 miles later. Or 206 miles later.